The Moose World

With the man who would be moose, Dr.Vince Crichton

Moose are an umbrella species — if we properly manage the moose in Manitoba, we will also be providing proper habitat for about 62% of the other wildlife species in the landscape.

I have seen over 30,000 moose in my time. They are an icon of the boreal forest, but they are having real difficulties today. Some may not like what I have to say, but I want to emphasize that the underlying theme of my comments is conservation. We must work together to pass on to future generations the bountiful legacy that our forefathers passed down to us.

My comments are the result of much reading, personal experience and observation, and my attempts to construct a systematic, coherent, and contemporary view of things. I do not pretend to have all the answers, but I like to think I am practical and a realist. At the same time, I possess an intense desire to protect the environment, including its wildlife resources, for the future.

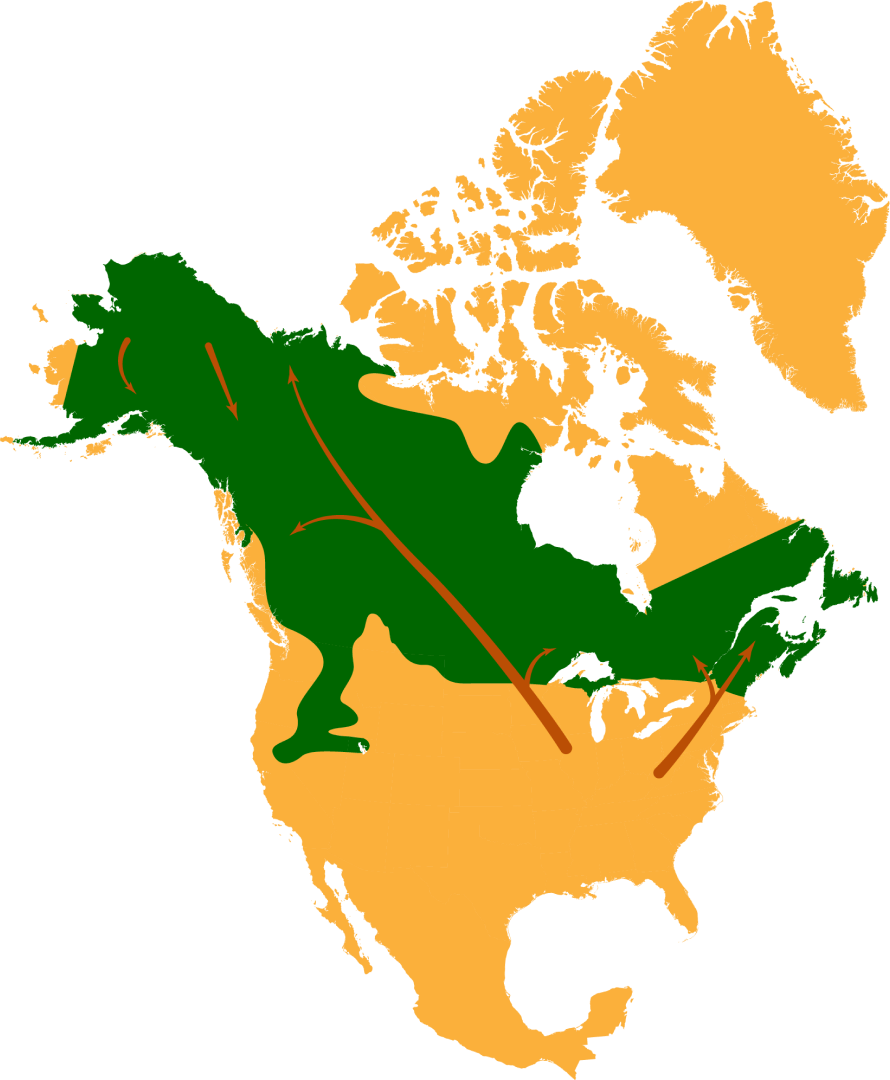

Where did moose come from? I had the good fortune, with my wife Kim, to be in Yakutsk in Eastern Siberia in 2008. This is where moose evolved, originally. Some of them went west, and some of them went east.

Moose came to this continent about 15,000 years ago, crossing the Bering Land Bridge, a 1,500-mile wide isthmus that connected what is now Asia to North America. The colonization of this continent was dictated by the ice sheets predominant at the time.

Routes of Moose Dispersal

Moose Habitat

Moose dispersed southward along an ice-free corridor created in the McKenzie River basin when the continental ice cap divided into two ice sheets: the Cordilleran ice sheet to the west and the larger Laurentide ice sheet to the east. Progressive melting then enabled moose to move south into new, emerging habitats as the ice retreated. They stratified themselves out on the southern part of the great ice sheets.

Moose have colonized many different types of habitats, from deserts to mountain terrain. Over time, they moved north into Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Northern Ontario, and the east coast of Canada. We now have four subspecies of moose in North America: the Alaska/Yukon moose, the Shiras moose, the Western Canada moose, and the Eastern Canada moose.

Moose artifacts collected from southern Manitoba and the Red River Valley have been aged at 4,500 years old.

Some moose artifacts collected from southern Manitoba and the Red River Valley are 4,500 years old.

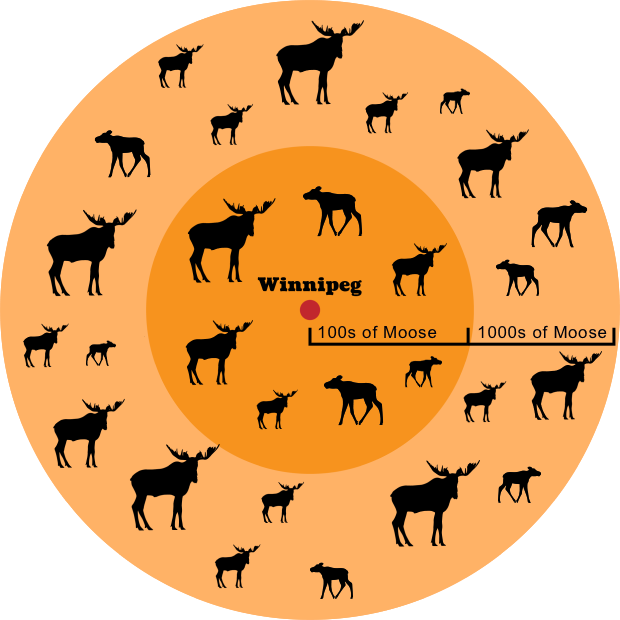

In 1900, it was reported in Manitoba that: “The moose is however, far from being scarce or in much danger of becoming extinct. I can safely say that within 50 miles of Winnipeg there are hundreds of moose; and that within 100 miles there are thousands of them.”

That was then. The population of moose in Manitoba has now declined from an historical high of over 45,000 animals to less than 20,000.

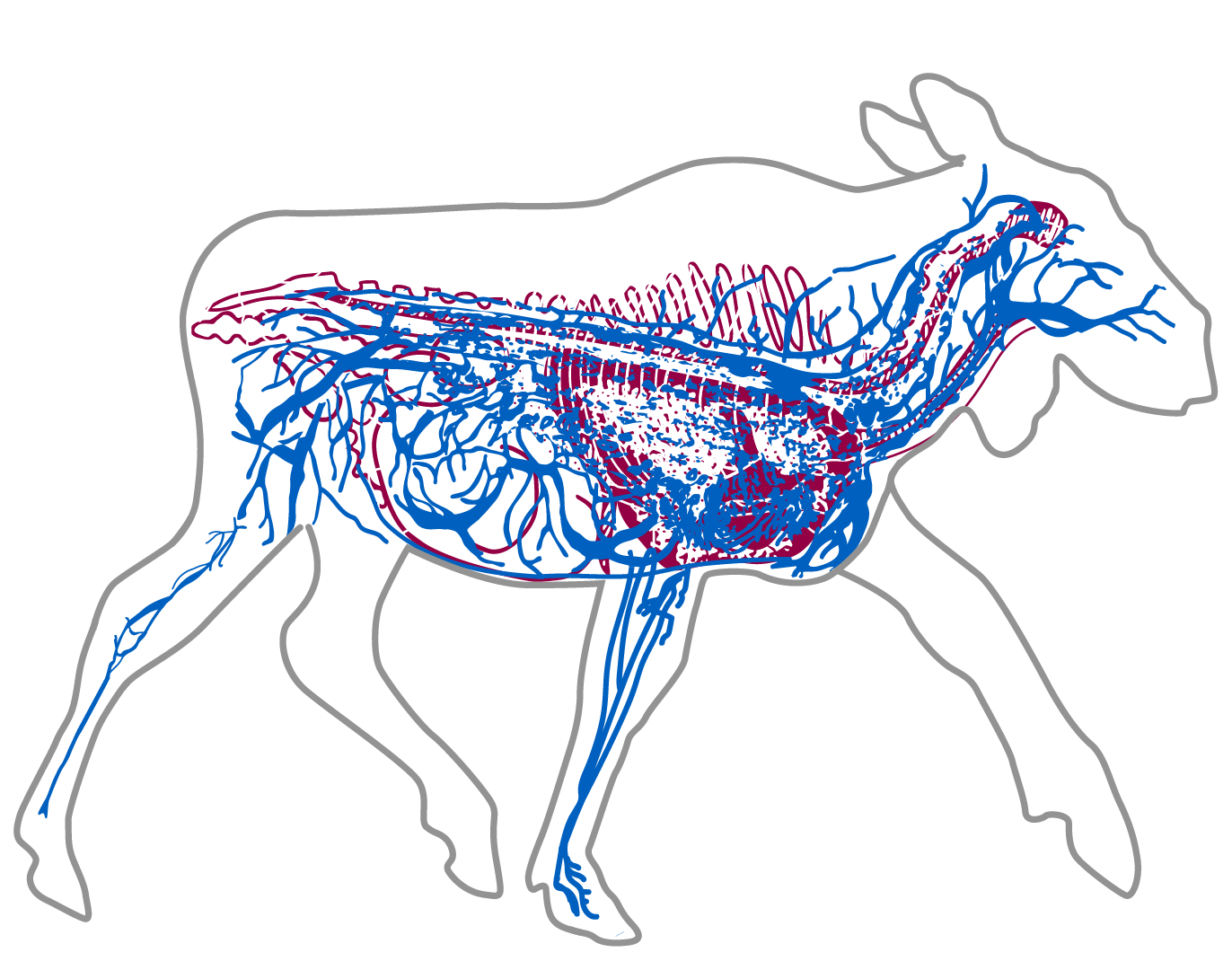

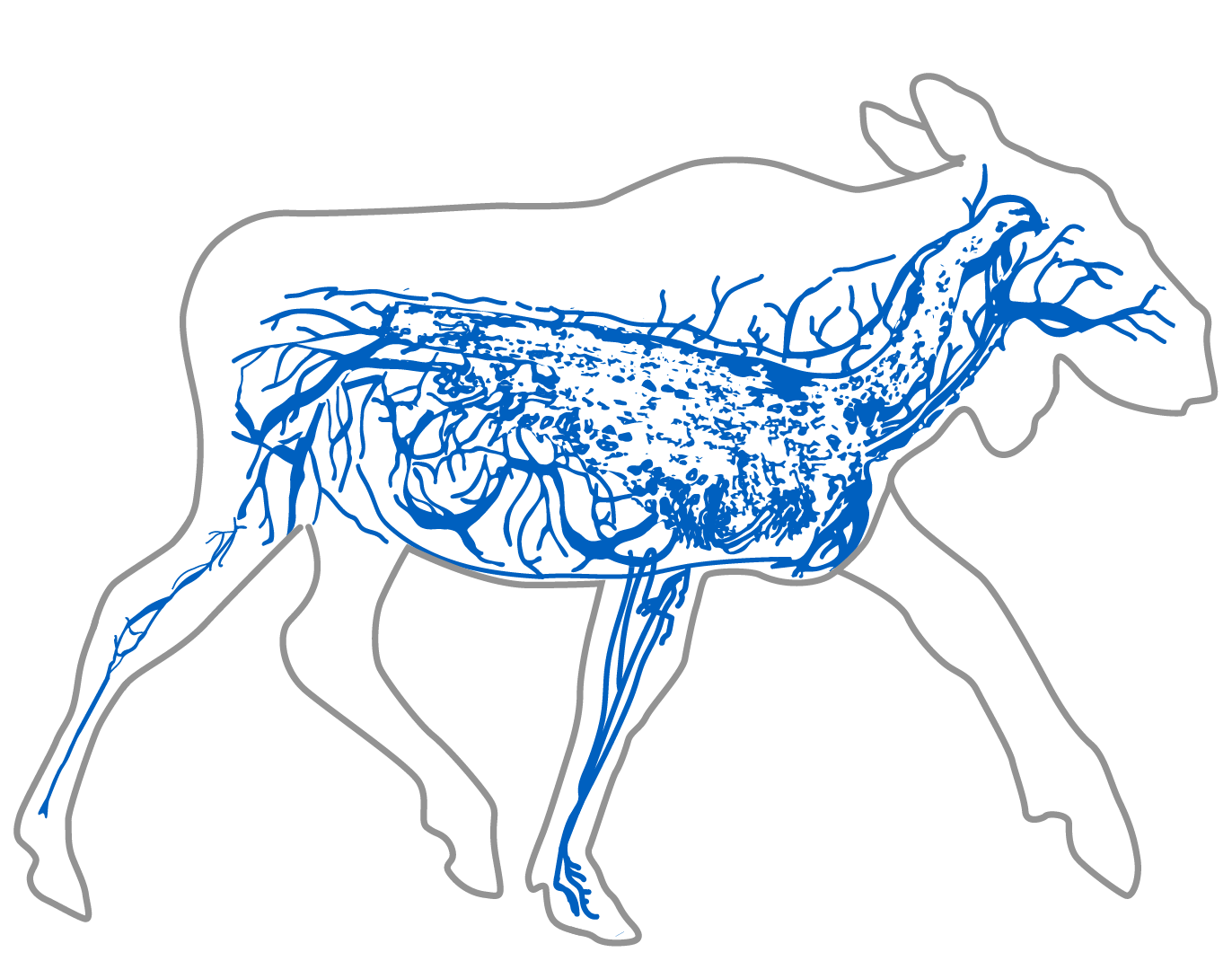

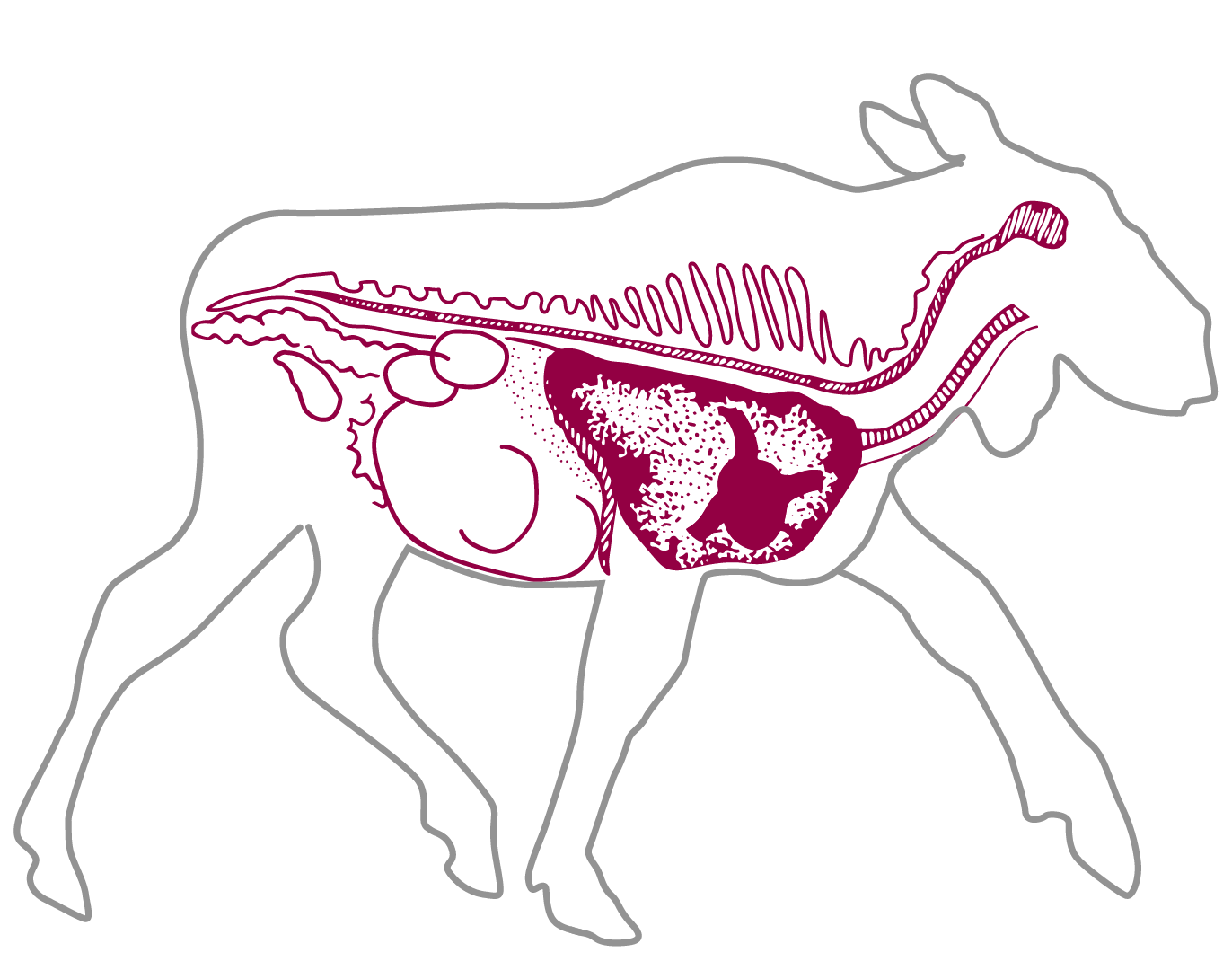

Moose Anatomy

Hover over the word to highlight the moose's body

Nervous System

Organs

Skeleton

Instead of judging the age of a bull moose by his antlers, we use his teeth. We grind them between two grindstones and count the rings on the teeth just like you do the rings on a tree.

Moose are browsers. Moose feed on succulent vegetation in summer, such as the leaves of aspen, birch, willow, black poplar, or red osier dogwood trees, to name just a few. Aquatic vegetation, such as yellow water lily, ribbon grass, and assorted pondweeds, make up a substantial part of their diet in late June and July.

A Year Measured in Antlers

Antlers start growing around the first part of April. Moose antlers are one of the fastest growing tissues.

I can tell you from sight whether a bull moose is one-and-a-half years old or two-and-a-half years old, and so on. But you cannot really tell the age of a moose when they get much older by looking at the antlers only.

Mature bulls can have what we call a split or butterfly-type antler between the main palm and the brow palm. Mature bulls can also have what we call a full palm antler where there is no indentation between the main palm and the brow palm.

As a mature bull grows older, beyond his prime years, his antlers may still measure the same spread but the mass of the antlers will decline.

Atypical antlers can occur when bulls are castrated. They are called peruke antlers, and I have heard such animals referred to as devil moose. Castration can happen because of disease or accidentally — from a barbed-wire fence, for instance.

Once castrated, the bull moose will shed his regular set of antlers and grow an atypical set that will never shed again. These antlers in some cases have a coral-like appearance.

I have weighed moose that were

1,600 pounds or 725 kilograms.

What happens when moose shed their antlers? Right at the growing point, between the antler and the skull, bone destroying cells invade. Osteoblasts are cells that create bone, whereas osteoclasts are bone-destroying cells. The only part of this animal that was still attached was right in the centre — when I happened to bump that antler with my hand, it popped off!

This is a really interesting one. Some traditional knowledge that I have been able to find: once a moose casts one antler, and the other is still there, the remaining antler causes such irritation that the moose will go up to a tree and bang it off.

Sometimes, part of the skull of the moose will come off with the antler, and then infection can get into the skull. If the animal survives, the pedicle may have been damaged so severely that the antler on the affected side will not grow the following year.

In early December, bull moose shed or cast their antlers: about 10% (usually older moose) do so by the end of the first week, followed by younger animals. This is the general rule, but when flying moose surveys I have seen bulls that still have large antlers in late January.

Language of Antlers

The only time antlers are used is during the rutting period in September. Moose use antlers to intimidate or threaten rivals in order to gain superiority, which may lead to breeding females and passing their genes to the next generation.

The Rut

The rutting period refers not just to the actual breeding (copulation) period, as some think, but a series of physiological and behavioural changes that cumulate with breeding.

Beginning in mid-August, the first evidence of the rut onset is a change in the colour of the facial hairs of bulls. Their summer colour is light brown, but as testosterone levels begin to build their colour changes to a dark brown/black.

The next event is velvet shedding, which starts around September 5th. This occurs first with mature bulls and then with teenagers a little later. That said, I have observed large bulls velvet-free as early as September 1st.

Another phenomenon is the cessation of feeding by bulls, which can last for up to 18 days. During this rutting period, bulls can lose from 12% to 20% of their pre-rut body weight. It should be noted that moose are in their best shape just as the rutting period commences.

The extent to which bulls advertise their sexual readiness is dependent on maturity, body mass, antler size, and breeding experience. Following velvet shedding, prime bulls broadcast their copulatory readiness with hiccup calls, making wallows, profuse salivation (nose dripping), and saturating the bell region and underside of their antlers with urine.

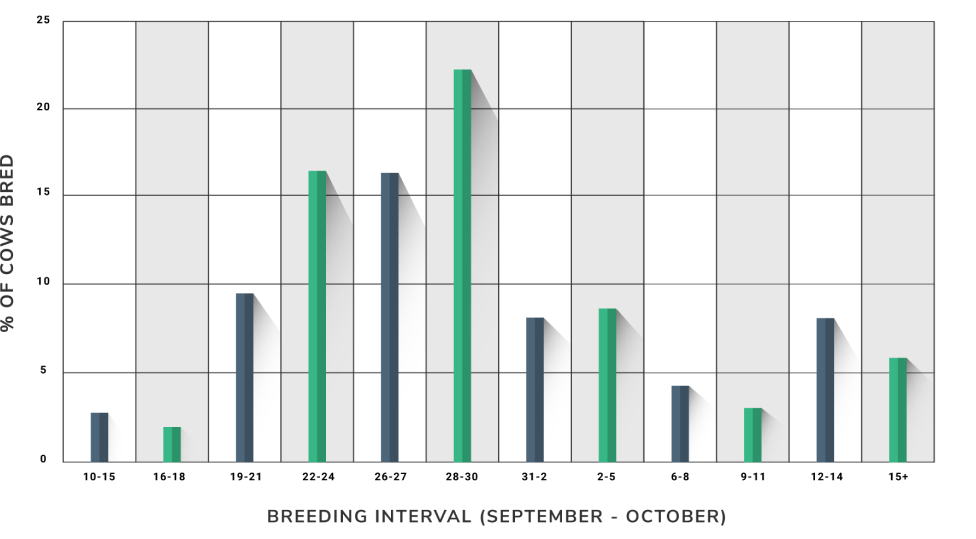

Breeding takes place in late September, assuming that you have an adequate number of mature bulls to “do the job.” The average breeding date is September 29th, with the median being September 26th.

This young fella is making a wallow. It is absolutely fascinating to watch. He will start to make the wallow (a depression in the ground) by pawing with his front feet. Then, he will try to urinate, but he cannot do it. It is unbelievable! After each bout of trying to urinate, he will commence digging again, sniff at the wallow, and repeat the process. Only on the seventh attempt will he be able to urinate.

Once he has urinated, he will splash his feet in it, and get that urine on his bell, and on the underneath side of his antlers. Bull moose urine has a very pungent odour — I call it “eau de moose” — and it really turns the cows on.

I had my granddaughter Julia with me early one morning in Riding Mountain National Park. We saw a big bull alongside the road, and he started going up the hill. I said, “Sweetie, watch this. It is something that not very many people are going to see.”

The big bull made his wallow, and the cow came over and gave him a lifter. And she laid down in the wallow, and rubbed herself in it, and they were happy and everything.

And so Julia went up to the wallow, and she said, “Grampy, this stinks.” So we get back to the truck, and she calls her grandmother. “Hey Grandma, guess what? We just saw a moose wallow.” She says, “Grampy gets so excited when he sees this.”

Once the rut is over, moose pregnancies last about 230 days. The peak of calving is the week of May 20th.

Of course, sometimes you'll have two bulls of the same social rank. The end result of this sometimes is animals that fight for the right to mate, and lock antlers during the fight, and end up dying.

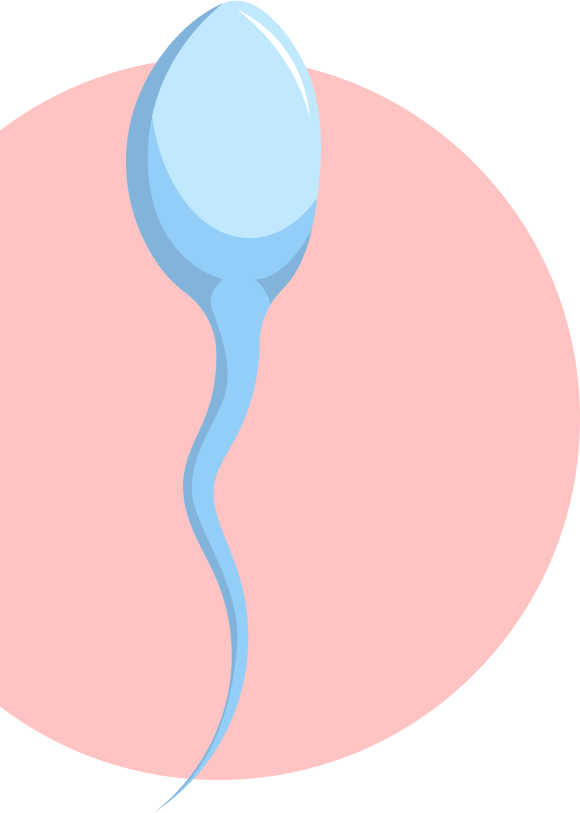

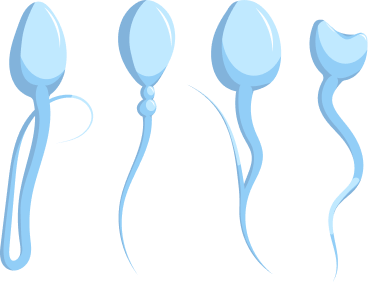

On the left, the sperm of a mature bull moose. On the right, the sperm of immature bull moose. Look at the anomalies in the sperm of the immature bull moose and realize that they cannot swim properly in seminal fluids to fertilize the egg.

That’s why we have got to make sure we have enough mature bulls out there during the breeding season.

What’s Killing Moose?

Ticks can kill moose. Not the common wood tick, but the winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus). How many winter ticks on one moose? One year in December, we found (on average) 56,000 winter ticks on calves, 39,000 winter ticks on cows, and 29,000 winter ticks on bulls. One unlucky bull had 96,000 winter ticks.

One spring, I sat and observed a moose for about two hours. When it got up and moved, I carefully searched the bedding site and found forty-eight fully engorged female ticks.

A high percentage of moose emerge from winter with varying degrees of tick-induced hair loss, in some cases well above 50%. In the spring of 2002, in the Aspen Parkland/western Manitoba area, about 40% of the moose population died due to a combination of heavy tick infestation and a long, cold, wet spring.

The moose hair shaft is dark toward the outer part but grey near the skin. With extensive grooming, the shaft breaks, so moose in the spring can appear greyish in colour due to the hair shaft being broken. These are referred to as “ghost moose.”

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is an incurable, always fatal degeneration of the brain. It can be transmitted by the body fluids of infected animals (urine, feces, and saliva). CWD is highly contagious and can spread to and through wild ungulate herds. It has been shown to persist and remain infectious in the environment.

Decomposing carcasses create contaminated “super-sites.” The CWD crisis is insidious, dire, and URGENT — requiring immediate, emergency-level response.

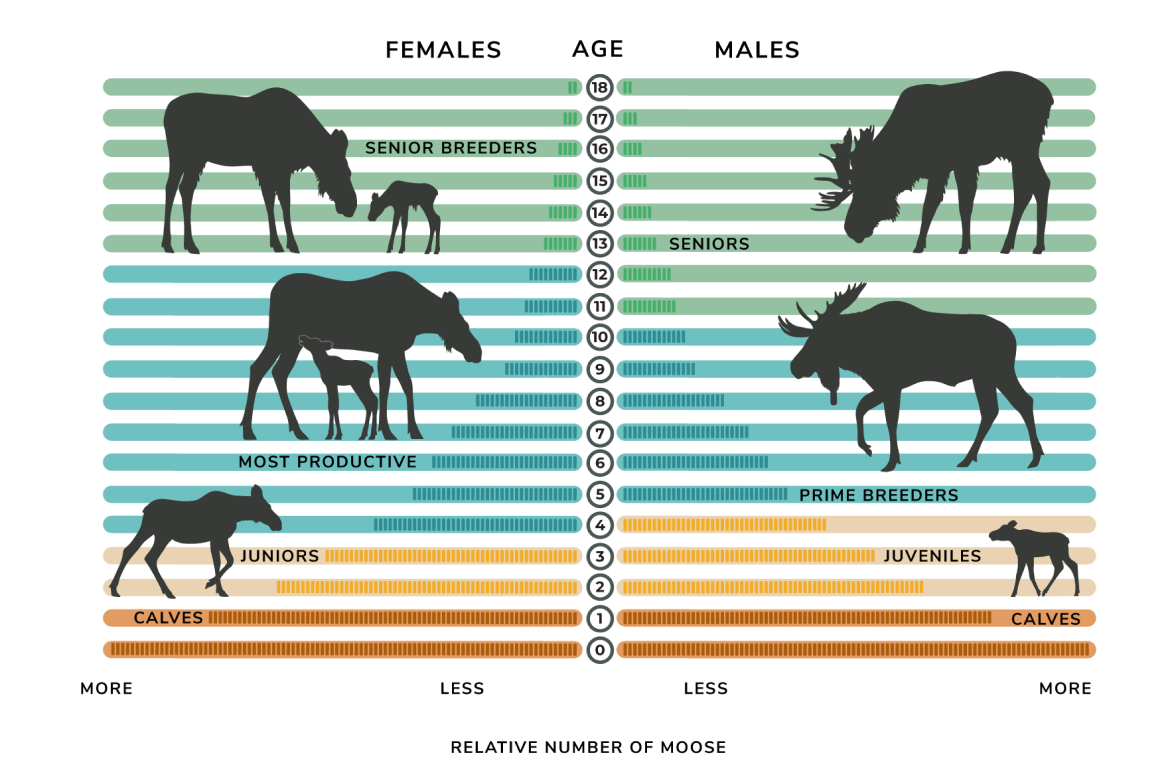

Social Structure

This is what a moose population looks like. We have a lot of calves out there, and many juveniles.

I just arbitrarily put these colours on here, to illustrate a concept to you. Notice how as we go up the chart, the numbers decline, so that it looks like a pointy pyramid. When populations go down, imagine chopping off the top of the pyramid. As populations decline, you keep chopping further and further down.

Eventually there’s no green left. The mature bulls are gone. The mature cows are gone, the ones that produce twins. You can see that as populations decline, which they have been doing, we end up with a real problem.

I just coloured this randomly to illustrate the concept, but these ranges are based on real data, and that’s the real math of it in broad strokes. This is a serious issue that requires serious action to save the moose.

Percentage of cow moose bred on 3-day intervals during September and October

I've looked at a lot of reproductive tracts. The average breeding date falls around the last three days of September. The latest I've found a moose to breed is November 21st. (I have that fetus in a vial at home. He's the size of my thumb.) The earliest date I’ve found was August the 21st. When populations go down, we can't be shooting cow moose. We use the term “recruitment” to refer to the number of calves that survive to one year of age and enter the adult population. If the rate of recruitment equals the rate of mortality, we've got a level population. If recruitment exceeds mortality, the population is going up. If mortality exceeds recruitment, the population is going down, which is unfortunately what we have been seeing.

The meningeal or brain worm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) is carried in whitetail deer and does not affect them at all. But brain worms are fatal in moose, and the whitetail deer and moose populations are increasingly overlapping.

Once brain worms reach the spinal column in moose, they enter tissue and often cause severe damage to the spinal column and other nerve tissues (e.g., nerves running to the eye). The damage often results in moose circling, blindness, and eventually death. However, some moose will overcome the infection and survive.

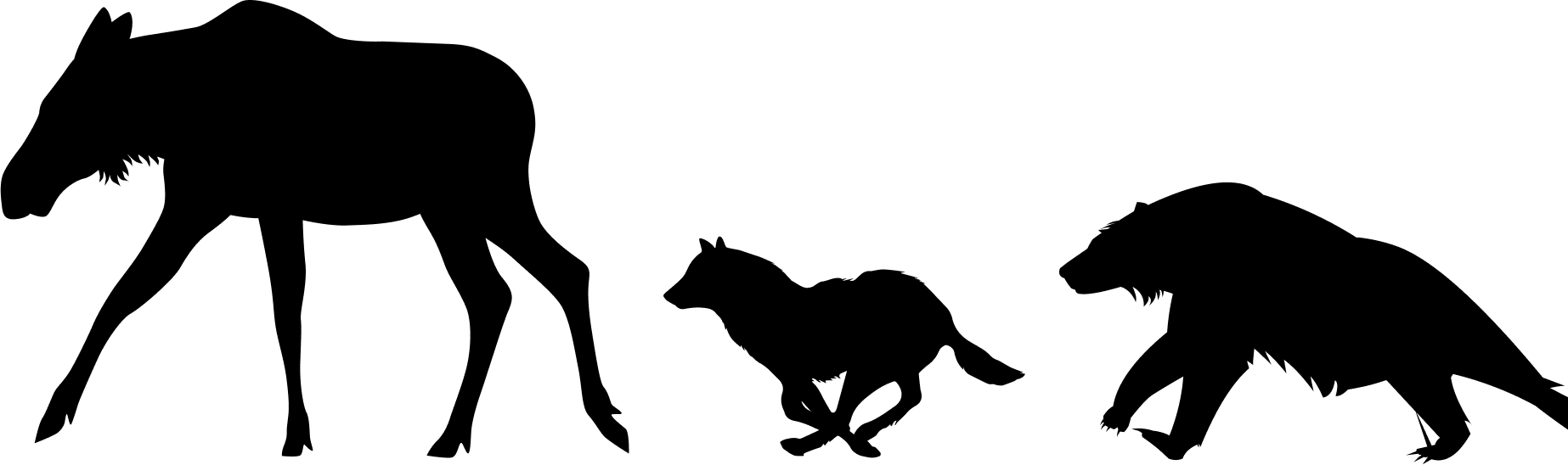

Predators

Black bears and wolves prey upon moose calves and animals weakened by disease or injury. The impact of predation on regulating moose populations is debatable; however, as moose numbers decline, the effect is accentuated.

Moose deaths from vehicles (cars and trains), fighting injuries, calf abandonment, drowning, entrapment (in holes, crevices, or deep snow), birthing issues, and injuries from slips and falls were once considered to be of little consequence — but research now suggests that they claim the lives of thousands of animals each year in North America.

As the rut becomes more intense, bulls that were friendly to each other during the summer period become extremely aggressive to old friends and fights occur between bulls of the same social rank. Additionally, fighters can lock antlers, which can cause death to both combatants.

Hunting

To answer a common question: yes, I am a hunter. I hunt with a firearm, cameras, and binoculars. I am a conservationist and I believe in sustainable use, but I also believe that we have to put restrictions on how all of society makes use of natural resources.

Ol’ Bullwinkle has not changed in the last 12,000 years. The moose still has fur, four feet, a big nose and antlers. Compare that to how humans have changed in the same time period. Look at what we have now: cars, trucks, ATVs, high-powered firearms, et cetera.

What chance does the moose have against us, if we have unfettered access to our gadgets? Also, what image does it send to those opposed to hunting if we carry on in a manner that does not reflect positively on hunting?

In 2000, 344,871 licensed hunters harvested 70,744 moose across Canada. The total estimated population at that time was 784,000 moose. In addition to regulated hunting, most jurisdictions see unregulated, rights-based hunting by different indigenous peoples, though the magnitude of this harvest is unknown. The impact of illegal poaching is also largely unknown and likely varies by region.

Hunting involves pursuit, but also enjoyment of fine mornings, of nights with the howl of the wolf — of the land, lakes and rivers, the sounds of nature, camp life in a tent, and the camaraderie of friends. All of these contribute to the makings of a successful hunt. A true hunt involves more than just a bounty in the freezer, and placing serious restrictions on hunting to protect moose won’t ruin the experience for hunters.

Moose & Forest Fires

Now, I want to illustrate what can happen when moose are exposed to young nutritious browse. Prior to a large fire in the late ’70s in the central Interlake area of Manitoba, we were averaging about 50 calves per 100 cows. After a large fire, light gets onto the ground and you get new growth coming up.

After females had been on this rejuvenated range for one full cycle, we were averaging about 100 calves per 100 cows. Due to the improved nutrition from the young trees, shrubs, and plants that grew after the fire, this population growth was sustained for four or five years with a very high twinning rate.

Activities such as forest fire suppression, reduced logging, and other forestry practices have an impact on the quality and quantity of moose habitat. In Ontario, fire suppression has had a dramatic impact on total acres burned and the supply of nutritious foods that follow such fires. Researchers found that about 1.54% of Ontario used to burn annually, but with fire suppression, only about 0.17% now burns.

Access

The effects of greater access to remote areas and new technology are cumulative and increase the risk of moose death. Hunters have all the advantages of all-terrain vehicles, snow machines, airplanes, GPS locators, high-powered firearms with enhanced optics, trail cameras, and drones. New road networks (often created for resource extraction) offer increased access and fragment habitat.

My friend, the late Tony Bubenick, gave me the idea to create an artificial bull moose head, for use in the field, to better study moose behaviour. I have a set of antlers that puts me in the upper echelon of the moose world. I call him Duffy. Duffy and I have had many interesting encounters.

The population of moose in Manitoba has now declined from an historical high of over 45,000 animals to less than 20,000. The only secure populations are either in roadless boreal and tundra areas, or are protected from harvest in areas such as Riding Mountain National Park and some private agricultural lands.

In modern times, unregulated hunting of a highly sought-after species that, by its very nature, is slow to reproduce, vulnerable to disease, requires high quality habitat, and is very vulnerable to modern human harvest tools, creates a very challenging management problem that requires a holistic, cooperative solution.

What is happening to the moose?

The declines in the moose population in Manitoba are substantial and not restricted to any particular region. Several factors contribute cumulatively to this decline in various areas, such as: overharvesting, lack of harvest protection for cows and calves, disease, parasites, predation, and increased human access.

It is also clear that moose populations are almost universally below available habitat capacity. Thankfully, because most declining moose populations are on Crown land, a concerted conservation effort might reverse these declines.